Oblate Articles

The following articles were written to assist oblates, employees, and friends of Mount Angel Abbey to incarnate our Benedictine spirituality in the broader Church and world. Such an incarnation naturally requires a lively engagement with the wellsprings of monastic spirituality, namely, Scripture, liturgy, and the patristic tradition. Accordingly, each of the following articles explores these sources in the context of Mount Angel’s distinctive charisms and apostolates. We pray that this “holy reading” might strengthen your communion with the monks of Mount Angel and shed light on your spiritual path.

“I Hated Them With a Perfect Hatred”

In Perelandra—the second book of C.S. Lewis’ lesser-known “Space Trilogy”—Elwin Ransom (the novel’s protagonist) finds himself on the newly-populated planet of Venus (“Perelandra” in their language). As the reader soon discovers, Ransom has been brought to this parallel Eden to preserve the innocence of a parallel Eve, the “Lady,” “Queen,” and “Mother” of her world. As one might expect, this brings Ransom into conflict with a parallel Serpent, Satan himself, who came to Perelandra in the body of the first book’s villain, attempting a repeat performance of his ancient victory on Earth (“Thulcandra”). As the conflict between Ransom and Satan escalates to physical violence—the preordained means by which Perelandra will be saved—Lewis describes a rather shocking development within his hero:

An experience that perhaps no good man can ever have in our world came over him—a torrent of perfectly unmixed and lawful hatred. The energy of hating, never before felt without some guilt, without some dim knowledge that he was failing fully to distinguish the sinner from the sin, rose into his arms and legs till he felt that they were pillars of burning blood… It is perhaps difficult to understand why this filled Ransom not with horror but with a kind of joy. The joy came from finding at last what hatred was made for. As a boy with an axe rejoices on finding a tree, or a boy with a box of coloured chalks rejoices on finding a pile of perfectly white paper, so he rejoiced in the perfect congruity between his emotion and its object… He felt that he could so fight, so hate with a perfect hatred, for a whole year. (288)

Shocking as it may sound, the above passage is little more than a dramatic enactment of Sacred Scripture—in particular, of King David’s curse against God’s enemies in Psalm 139:22: “I hated them with a perfect hatred.” Such a sentiment—as any student of Scripture well knows—shows up again and again throughout the Psalms, rearing its ugly head even in the midst of otherwise-pleasant passages. Reflecting on perhaps the most infamous of such instances—“the horrible passage in [Psalm] 137 about dashing the Babylonian babies against the stones”—Lewis makes a Christian case for “perfect hatred”:

I know things in the inner world which are like babies; the infantile beginnings of small indulgences, small resentments, which may one day become dipsomania or settled hatred, but which woo us and wheedle us with special pleadings and seem so tiny, so helpless that in resisting them we feel we are being cruel to animals. They begin whimpering to us “I don’t ask much, but,” or “I had at least hoped,” or “you owe yourself some consideration.” Against all such pretty infants (the dears have such winning ways) the advice of the Psalm is the best. Knock the little bastards’ brains out. And “blessed” he who can, for it’s easier said than done. (136)

For Lewis—as for any conscientious Christian—the Israelites’ violent hatred would, indeed, be deplorable if it were directed only toward their earthly enemies. Did not Christ, after all, command his disciples to “love [their] enemies and pray for those who persecute [them]” (Matthew 5:44)? When directed, however, at one’s own sinful inclinations, hatred becomes not only appropriate but imperative.

This “perfect hatred” is by no means peculiar to Lewis. On the contrary, it was commended by virtually all of the earliest monks. Saint Benedict, for example, interpreted Psalm 137 in precisely the same way as Lewis, not once but twice exhorting his monks to catch hold of their nascent temptations and dash them against the rock who is Christ (cf. Prologue 28; 4.50). Saint John Cassian—whose works were required reading for Benedict’s monks (RB 42.3; 73.5)—understood the biblical injunction to “be angry but do not sin” (Psalm 4:5; Ephesians 4:26) as a command “to get angry in a healthy way, at ourselves and at the evil suggestions that make an appearance, and not to sin by letting them have a harmful effect” (Institutes 8.9). Most strikingly of all, Evagrius of Pontus—Cassian’s teacher in the Egyptian desert—asserted that “hatred against the demons contributes greatly to our salvation and is advantageous in the practice of virtue” (On Thoughts 10). Commenting on Psalm 139—the same Psalm that inspired Ransom’s “perfect hatred” in Perelandra—Evagrius explained that “he hates his enemies with a perfect hatred who sins neither in act nor in thought” (On Thoughts 10). Indeed, Ransom’s “perfect hatred” is perfectly in keeping with the advice Evagrius offered to one budding monk, Eulogios:

Prepare yourself to be gentle and also a fighter, the first with respect to one of your own race and the second with respect to the enemy; for the usage of irascibility lies in this, namely, in fighting against the serpent with enmity (cf. Genesis 3:15), but with gentleness and mildness exercising a charitable patience with one’s brother while doing battle with the thought. (To Eulogios 11.10)

Having proved himself a fighter against the “ancient serpent” (cf. Revelation 12:9) and gentle toward every living thing on Perelandra—most especially the Lady in her time of trial—Ransom is revealed to be not only a figure of Christ but also a fitting embodiment of monastic—i.e., Christian—spirituality.

———–

Further reading:

- C.S. Lewis. The Space Trilogy: Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength. Quality Paperback Book Club, 1997.

- C.S. Lewis. Reflections on the Psalms. Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1958.

- John Cassian. The Institutes. Translated by Boniface Ramsey. The Newman Press, 2000.

- Evagrius of Pontus. The Greek Ascetic Corpus. Translated by Robert E. Sinkewicz. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Article Archive

-

Happy... Deathday?

Happy… Deathday?

The monks of Mount Angel keep (on paper, at least) the countercultural custom of refusing to celebrate birthdays. Although the practice may sound curmudgeonly, its roots are, in fact, deeply spiritual, arising from no lesser source than Sacred Scripture. As early as the third century, Origen of Alexandria—the great pioneer of lectio divina—devoted considerable attention to biblical birthdays in his Homilies on Leviticus:

Not one from all the saints is found to have celebrated a festive day or a great feast on the day of his birth. No one is found to have had joy on the day of the birth of his son or daughter. Only sinners rejoice over this kind of birthday. For indeed we find in the Old Testament Pharaoh, king of Egypt, celebrating the day of his birth with a festival [cf. Genesis 40:20], and in the New Testament, Herod [cf. Mark 6:21]. However, both of them stained the festival of his birth by shedding human blood. For the Pharaoh killed “the chief baker” [cf. Genesis 40:22], Herod, the holy prophet John “in prison” [cf. Mark 6:27]. But the saints not only do not celebrate a festival on their birth days, but, filled with the Holy Spirit, they curse that day. (8.3.2)

Origen goes on to quote Jeremiah (20:14: “Cursed be the day on which I was born!”), Job (3:3: “Perish the day on which I was born!”), and the famous confession of King David in Psalm 51 (v. 7: “Behold, I was born in guilt”). All of these biblical heroes, in stark contrast to Scripture’s wicked kings, eschewed vanity and pride in favor of penitence and humility. Their striking witness was, for Origen and his hearers, a sign of contradiction to the extravagant dies natalis (literally “birth day”) celebrations observed in honor of Roman emperors and pagan gods.

Earlier still than Origen, the first- and second-century “Apostolic Fathers” had already begun turning the dies natalis on its head. Ignatius of Antioch, for example, described his impending martyrdom in terms not of death but of birth: “The pangs of new birth are upon me. Forgive me, brethren. Do nothing to prevent this new life. Do not desire that I shall perish… Allow me to receive the pure light. When I reach it, I shall be fully a man.” (To the Romans, 6) The Christian community of Smyrna used similar language to describe the fate of their martyred bishop, Polycarp: “Afterwards, we took up his bones, more valuable than precious stones and finer than gold, and put them in a proper place. There, as far as we [are] able, the Lord will permit us to meet together in gladness and joy and to celebrate the birthday of his martyrdom.” (Martyrdom of Polycarp, 18.2–3)

Such paradoxical accounts of death-as-birth resulted in a radical redefinition of the “dies natalis.” No longer did a Christian’s “birthday” commemorate the day on which he or she came forth from the womb; rather, one’s real “birthday” was the day on which one was born (or “born again” / “born from above” [cf. John 3:3]) into the fullness of life in heaven. The Church definitively enshrined this theological redefinition of the dies natalis in her liturgical calendar by fixing the “feast day” for most saints—including Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp of Smyrna—as the day on which they passed from this life to the next. By celebrating such “birthdays” year after year, believers are meant to ponder, more and more deeply, the mystery of death and life in Christ.

Such reflection, however, need not occur only on the feasts of saints. For the thoughtful Christian, even an ordinary birthday can prompt extraordinary spiritual reflection. Such was certainly the case for George MacDonald—the 19th-century pioneer of fantasy literature and a leading influence on the likes of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Writing to his eldest daughter, Lilia, on the occasion of her 21st birthday, his well-wishes were anything but superficial:

My Darling Goose,

…

May you have as many happy birthdays in this world as will make you ready for a happier series of them afterwards, the first of which birthdays will be the one we call the day of death down here. But there is a better, grander birthday than that, which we may have every day—every hour that we turn away from ourselves to the living love that makes our love, and so are born again. And I think that all these last birthdays will be summed up in one transcending birthday, far off it may be, but surely to come—the moment where we know in ourselves that we are one with God, are living by his life, and having neither thought nor wish but his—that is, desire nothing but what is perfectly lovely, and love everything in which there is anything to love. (An Expression of Character: The Letters of George Macdonald, 235)If George MacDonald has gone against the grain by speaking of death on his daughter’s birthday, then he finds himself in good company. Like the aforementioned biblical heroes and the fathers of the early Church, MacDonald employed paradoxical, countercultural language to raise his daughter’s eyes (and the eyes of all who would later read his letters) from the passing joy of a worldly birthday to the surpassing joy of “a better, grander birthday”—“the one transcending birthday”—of perfect union with “the living love that makes our love.”

Surely this is what Saint Benedict had in mind when he instructed his monks—not just on their birthdays, but “daily”—“to keep death before [their] eyes” (RB 4.47).

———–

Further reading:

- Origen of Alexandria. Origen: Homilies on Leviticus 1–16. Translated by Gary Wayne Barkley. The Catholic University of America Press, 1990.

- The Apostolic Fathers. Translated by Francis X. Glimm, Joseph M.-F. Marique, and Gerald G. Walsh. The Fathers of the Church. The Catholic University of America Press, 1947.

- George MacDonald. An Expression of Character: The Letters of George Macdonald. Eerdmans, 1994.

-

“Chocolate Eggs and Jesus Risen”

“Chocolate Eggs and Jesus Risen”

In one of his Reflections on the Psalms, C.S. Lewis—the celebrated Christian apologist, novelist, and literary scholar—pauses to consider the profundity of a young child’s Easter “poem”:

I have been told of a very small and very devout boy who was heard murmuring to himself on Easter morning a poem of his own composition which began “Chocolate eggs and Jesus risen.” This seems to me, for his age, both admirable poetry and admirable piety. But of course the time will soon come when such a child can no longer effortlessly and spontaneously enjoy that unity. He will become able to distinguish the spiritual from the ritual and festal aspect of Easter; chocolate eggs will no longer be sacramental. And once he has distinguished he must put one or the other first. If he puts the spiritual first he can still taste something of Easter in the chocolate eggs; if he puts the eggs first they will soon be no more than any other sweetmeat. They have taken on an independent, and therefore a soon withering, life. (48–49)

On a purely natural level, chocolate eggs are delightful. Like bread, wine, and oil—anything, in fact, that we might call “fruit of the earth and work of human hands”—they were conceived by God for our sustenance and joy. As the Psalmist puts it: “[You] bring forth food from the earth, wine to gladden their hearts, oil to make their faces shine, and bread to sustain the human heart” (Psalm 104:15–15). On a sacramental level, however, chocolate eggs are doubly delightful. All the imperfect-yet-no-less-real joy we experience in this “festal” aspect of Easter is taken up by God to serve as a symbolic foretaste of the “spiritual” joy offered to us in the risen Jesus.

Some readers, however, might scoff at Lewis’ description of chocolate eggs as “sacramental.” Unlike bread, wine, and oil—all of which are assigned profound symbolic significance in the Church’s liturgical rites—chocolate eggs could be seen as tokens of a secular, commercialized culture creeping into the sacred season of Easter. Lewis, however, was not concerned in his reflection with liturgical propriety, but with the delight he saw on display in the Psalms—“the delight in God which made David dance” (45; cf. 2 Samuel 6:14). For Lewis, a child’s spontaneous delight in chocolate eggs, effortlessly and indissolubly united to his delight in Jesus risen, serves as a perfect Christian parallel to that delight the psalmist so often takes in the very means by which the Lord is praised: with harp and lyre, tambourine and dance, strings and pipes, blasting horns and crashing cymbals (cf. Psalm 150). To enjoy all this is nothing less than “to behold the fair beauty of the Lord” (Psalm 27:4).

A similar sentiment was expressed by Robert Taft—the late, great liturgical theologian—when he declared that “there is no law against liturgy being enjoyable” (The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West, 185). This phrase served as Taft’s commentary on the immense popular appeal (strange as it may sound to modern churchgoers) of all-night prayer vigils in late antiquity. By way of illustration, Taft reproduced the testimony of a layman, Sidonius of Apollinaris (later ordained bishop of Clermont), whose delightful description of a particular vigil is blessedly preserved for posterity:

We had gathered at the tomb of St. Justus… [where] the anniversary celebration of the procession before daylight was held. There was an enormous number of people of both sexes, too large a crowd for the very spacious basilica to hold even with the expanse of covered porticoes that surrounded it. After the vigil service was over, which the monks and clergy had celebrated together with alternating strains of sweet psalmody, everyone withdrew in various directions, but not far, as we wanted to be present at the third hour when mass was to be celebrated by the priests…

By and by, having for some time felt sluggish for want of exertion, we resolved to do something energetic. Thereupon we raised a twofold clamour demanding according to our ages either ball or gaming-board, and these were soon forthcoming. I was the leading champion of the ball; for, as you know, ball no less than book is my constant companion. On the other hand, our most charming and delightful brother, Domnicius, had seized the dice and was busy shaking them as a sort of trumpet-call summoning the players to the battle of the box. We on our part played with a troop of students, indeed played hard until our limbs, deadened by inactive sedentary work, could be reinvigorated by the healthful exercise…

Scarcely had [these things been done] when it was announced that the bishop, at the beckoning of the appointed hour, was proceeding from his lodging, and so we arose. (184–185; Letter 5.17)No one who reads the above description of a prayer vigil will be surprised by Sidonius’ talk of “sweet psalmody” or mass “celebrated by the priests.” We might be taken aback, however, by his emphasis on “ball” and “gaming-board” (to say nothing of the “pleasant, jesting, bantering” conversation that he describes at some length in the sections of his letter not reproduced above). Yet, just as C.S. Lewis could see chocolate eggs as sacramentals in the service of the Easter season, so too did Sidonius experience “ball” and “gaming-board” as sacramental realities for the vigil of St. Justus. Sidonius’ “spiritual” delight in psalmody and mass was evidently of a piece with his “festal” delight in ball and gaming-board.

It may be overly anachronistic to imagine “ball” and “gaming-board” as “soccer” and “Settlers of Catan,” but both activities have been known to happen—between hours of liturgical prayer—here at Mount Angel Abbey and Seminary. Yet even more representative of Sidonius’ vigil experience is our annual Saint Benedict Festival, held each year on the Saturday nearest the Solemnity of Saint Benedict (July 11). It consists of four hours of conviviality with the monastic community, bookended by Midday Prayer and Vespers. Insofar as such delightful festivities draw us to delight in God and one another (or to delight in God in one another), they are not so different from a child’s chocolate eggs at Easter time.

———–

Further reading:

- C.S. Lewis. Reflections on the Psalms. Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1958.

- Robert Taft. The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West: The Origins of the Divine Office and Its Meaning for Today. Liturgical Press, 1993.

- Saint Benedict Festival 2025. mountangelabbey.org/join-us/sbf/

-

“O Come, Let Us... Weep?”

“O Come, Let Us… Weep?”

On April 6, the Mount Angel Chamber Choir began its public performance with a selection from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil: “O Come, Let Us Worship.” Appropriately, the piece takes up the words of Psalm 95—the “invitatory” for Vigils each day—imploring the gathered assembly to offer due homage to God: “O Come, let us worship and fall down and kneel before the Very Christ, our God and Maker” (Psalm 95:6, as phrased by Winfred Douglas in his English arrangement of Rachmaninoff’s Russian composition). Perhaps more familiar to the monks of Mount Angel is Abbot Bonaventure Zerr’s rendering of the verse: “Come, bow before him in worship, kneel before the Lord who created us, for he is our God.”

However one chooses to translate the original Hebrew of Psalm 95:6, most modern English editions preserve some connection between praise of God and the bending of one’s knee. Yet, when this verse was first translated into Greek (in the 3rd-century BC “Septuagint,” often abbreviated “LXX”), the Hebrew word for “kneel” (בָּרַךְ, barak) was changed to “weep” (κλαίω, klaiō). This modified sense of the Psalm was inherited by the earliest Christians (whose lingua franca, so to speak, was Greek), and it was later enshrined in Saint Jerome’s 4th-century AD Latin translation of the Bible, the “Vulgate” (which employed the verb plōro, meaning “to cry out” or “weep aloud”).

Thus, when the earliest monks (or monastically-minded bishops) quoted Psalm 95, it was usually on account of its mournful overtones. St. Gregory of Nazianzus, for example, turned to the words of Psalm 95 to address his congregation in the aftermath of three back-to-back natural disasters: “Come then, all of you, my brethren, let us worship and fall down, and weep before the Lord our Maker [Ps 95:6]; let us appoint a public mourning, in our various ages and families, let us raise the voice of supplication” (Oration 16.14). In more mundane circumstances, Horsiesios (the second successor to St. Pachomius) cited Psalm 95 when describing the interior disposition that ought to accompany outward forms of monastic prayer:

When the signal is given for prayer, let us rise promptly; and when the signal is given to kneel, let us prostrate promptly to adore the Lord, having signed ourselves before kneeling. When once we are prostrate on our face, let us weep in our heart for our sins, as it is written, Come, let us adore and weep before the Lord our maker [Ps 95:6]… Let each one of us say in his heart with an interior sigh, ‘Purify me, O Lord, from my secret sins; keep your servant from strangers. If these do not prevail over me, I shall be holy and free from a great sin [Ps 19:13–14]; and, Create a pure heart in me, God, let a right spirit be renewed in my innermost self [Ps 51:10]. (Pachomian Koinonia: Pachomian Chronicles and Rules, 199–200)

By interpreting Psalm 95 in such a markedly penitential way, Gregory and Horsiesios bear witness to the ancient monastic preoccupation with “penthos,” a salutary sorrow leading to repentance. Placing their trust in Christ’s declaration that “blessed are they who mourn [penthountes]” (Matthew 5:4), the early monks zealously cultivated penthos and its associated phenomena of compunction (katanuxis) and tears (dakruōn). One such monk asked the 4th-century Abba Poemen, “What am I to do about my sins?” The holy elder replied, “One who wishes to release himself from sins is released from them by weeping.” He then went on: “Weeping—that is the way Scripture and our fathers delivered to us, saying, ‘Weep! For there is no other way but that one’” (The Book of the Elders: Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 3.29–30; cf. James 4:9). Evagrius of Pontus, another father of the Egyptian desert (and by no means a bleeding heart!), offered much the same advice: “First, pray for the gift of tears [dakruōn], to soften by compunction [penthos] the inherent hardness of your soul, and then, as you confess your sinfulness to the Lord, to obtain pardon from him” (quoted in Irénée Hausherr, Penthos, 24). In the Egyptian desert, penthos was paramount.

This venerable Egyptian tradition was subsequently taken up by Saint Benedict, who sought to share it with his own Western monks. The theme appears most prominently in chapter 49 of his Holy Rule, wherein he describes “the observance of Lent”:

We urge the entire community during these days of Lent to keep its manner of life most pure and to wash away in this holy season the negligences of other times. This we can do in a fitting manner by refusing to indulge evil habits and by devoting ourselves to prayer with tears, to reading, to compunction of heart and self-denial. (49.2–4; emphasis added)

Penthos, however, was not just meant for the Lenten season. As Benedict notes at the beginning of the same chapter, “the life of a monk ought to be a continuous Lent” (RB 49.1) Thus it is that Benedict instructs his monks to “every day with tears and sighs confess your past sins to God in prayer” (RB 4.57). To assist his monks with this daily practice of penthos, he prescribes the chanting of Psalm 51—the penitential Psalm par excellence—every day at Lauds (RB 12–13). For the same reason (we may presume), he also prescribes the chanting of Psalm 95—with its injunction to weep before the Lord—every morning at Vigils (RB 9).

Modern English translations of Psalm 95 (based as they are on the original Hebrew text) no longer include the word “weep,” but this has done nothing to dislodge the Psalm from its prominent place at the beginning of each liturgical day. For those of us attuned to the monastic tradition, the chanting of Psalm 95 still has the power to prompt in us a very Benedictine spirit of penthos.

———–

Further reading / listening:

- Sergei Rachmaninoff. “All-Night Vigil” (Op. 37). Phoenix Chorale.

- “Sorrow for Sin [Katanyxis, ‘Compunction’].” In The Book of the Elders: Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Translated by John Wortley. Liturgical Press, 2012. Pages 25–37.

- “The Regulations of Horsiesios.” In Pachomian Koinonia: Pachomian Chronicles and Rules. Translated by Armand Veilleux. Cistercian Publications, 1981. Pages 197–223.

- Irénée Hausherr. Penthos: The Doctrine of Compunction in the Christian East. Translated by Anselm Hufstader. Cistercian Publications, 1982.

-

“The Pure Love of Brothers”

“The Pure Love of Brothers”

In a climactic scene from The Iliad—Homer’s epic retelling of the Trojan War—Achilles is informed that his dearest friend, Patroclus, had been slain in battle. Upon receiving this news, “Achilles groaned, heartbroken,” “howled in agony,” and offered a series of moving laments:

My friend Patroclus, whom I loved, is dead. I loved him more than any other comrade. I loved him like my head, my life, myself… My dearest love! My poor, unlucky friend! … Nothing else could ever be worse for me than this. This is far worse than if I found out that my father died… The loss of you is far more terrible than if I learned that my dear son was dead… (18.99–101; 19.412–430)

Achilles’ agonized account of his love for Patroclus may sound a bit melodramatic to modern ears. In antiquity, however, it was not so. Intimate friendships were cultivated, celebrated, and commemorated in song—not only by the pagan Greeks, but also by God’s chosen people. King David, for example, uttered an Achilles-like lament for Jonathan, the son of Saul, when he heard that the one whom “he loved… as his very self” (1 Samuel 18:1) had fallen in battle: “I grieve for you, Jonathan my brother! Most dear have you been to me; more wondrous your love to me than the love of women” (2 Samuel 1:26).

This language of intimate, brotherly love is ubiquitous also in the Christian tradition. Perhaps the most iconic example is encountered every year on January 2, when the Roman Church celebrates the conjoined memorial of saints Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus (“the Theologian”). In a fourth-century funeral oration (again, reminiscent of Achilles), Gregory describes the intimacy he enjoyed with his beloved friend, Basil:

Basil and I were both in Athens… Such was the prelude to our friendship, the kindling of that flame that was to bind us together. In this way we began to feel affection for each other. When, in the course of time, we acknowledged our friendship and recognized that our ambition was a life of true wisdom, we became everything to each other: we shared the same lodging, the same table, the same desires, the same goal. Our love for each other grew daily warmer and deeper… We seemed to be two bodies with a single spirit. (Liturgy of the Hours, Office of Readings for January 2, the Memorial of Saints Basil the Great and Gregory Nazianzus)

Such a saintly pairing was by no means unique, however. With almost identical language, Saint John Cassian—whose Conferences and Institutes are required reading for every Benedictine monk (cf. Rule of Benedict 42.3; 73.5)—recounts what “everyone used to say” about him and his fellow monastic pilgrim, Germanus: “we were one mind and soul inhabiting two bodies” (Conferences 1.1.1). Later, while introducing an entire conference “on friendship,” he further defines his relationship with Germanus: “we were joined not by a fleshly but by a spiritual brotherhood” (2.16.1).

The “spiritual brotherhood” shared by Basil and Gregory, John Cassian and Germanus, and countless others like them spawned—in the Orthodox churches, at least—a special liturgy for “brother-making” (adelphopoiesis). When two men (or women, for that matter) wished to cement their fraternal bond, the church would pronounce a formal blessing over them:

Lord God… who has deemed it right that your holy and most famous apostles Peter, the head, and Andrew, and James and John the sons of Zebedee, and Philip and Bartholomew, become each other’s brothers, not bound together by nature, but by faith and through the Holy Spirit, and who has deemed your holy martyrs Sergius and Bacchus, Cosmas and Damian, Cyrus and John worthy to become brothers:

Bless also your servants [N] and [N], who are not bound by nature, but by faith. Grant them to love one another, and that their brotherhood remain without hatred and free from offense all the days of their lives… (Claudia Rapp, Brother-Making in Late Antiquity, 83)

Such a “brother-making” rite never took root in the churches of the West, but the fraternal love that underlies it is an unmistakable hallmark of Benedictine monasticism. In fact, the word “brother” (or some form of it) occurs precisely 100 times in Saint Benedict’s Holy Rule, largely because “brother” was Benedict’s preferred word for describing or addressing a “monk.” So central was brotherly love to Benedict’s monastic vision that it epitomized the “good zeal of monks” prescribed by Benedict in the penultimate chapter of his Rule:

No one is to pursue what he judges better for himself, but instead, what he judges better for someone else. To their fellow monks they show the pure love of brothers [caritatem fraternitatis caste]; to God, loving fear; to their abbot, unfeigned and humble love. Let them prefer nothing whatever to Christ, and may he bring us all together to everlasting life. (72.7–12)

In a culture increasingly consumed by ideologies, individualism, and mutual hostility, a rediscovery of “the pure love of brothers” is, perhaps, the timeliest gift that Benedictine monks can share with the Church and the world.

———–

Further reading:

- The Iliad. Translated by Emily Wilson. W. W. Norton & Company, 2023.

- Gregory of Nazianzus. “On St. Basil the Great” (Oration 43). In Funeral Orations. Translated by Leo P. McCauley. The Catholic University of America Press, 1953. (For an abridged version, quoted above, see: The Liturgy of the Hours, Office of Readings for January 2, the Memorial of Basil the Great and Gregory Nazianzus)

- John Cassian. John Cassian: The Conferences. Translated by Boniface Ramsey. Newman Press, 1997.

- Rapp, Claudia. Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium: Monks, Laymen, and Christian Ritual. Oxford University Press, 2016.

-

Whence Came the West’s First Christmas Carol? (Or: The Birth of an Ambrosian Hymn)

Christmas 2024 Whence Came the West’s First Christmas Carol? (Or: The Birth of an Ambrosian Hymn)

Four times in his Holy Rule, Saint Benedict instructs his monks to chant “an Ambrosian hymn” (RB 9.4, 12.4, 13.11, and 17.8). Whether he had in mind particular hymns penned by Saint Ambrose himself, or any similar chant employing alternating, antiphonal verses, we do not know. We do know, however, that Ambrose’s introduction of hymn-singing into the 4th-century Western church was wildly popular—so popular, in fact, that Ambrose’s original hymns have spawned hundreds of subsequent imitations.

Scholars are still spilling ink over which hymns Ambrose himself may have written, but four in particular are universally attributed to him: 1) Aeterne rerum conditor; 2) Iam surgit hora tertia; 3) Deus creator omnium; and 4) Intende qui regis Israel. Of these four, three are chanted to this day by the monks of Mount Angel Abbey: 1) Aeterne rerum conditor (“Maker of all, eternal king,” at Lauds on Sunday, week 1); 2) Deus creator omnium (“O God, Creator of all things,” at Vespers on Saturday, week 1); and 3) Intende qui regis Israel, whose first verse fell off to become Veni, redemptor gentium (“Redeemer of all nations, come,” at Vigils from December 17–24).

As the new name of the final hymn suggests, Veni, redemptor gentium has become a fixture of the Advent season. Originally, however, it was sung on December 25—the solemnity of the Nativity of the Lord—just as that feast was emerging in the 4th-century Western church. Saint Augustine bears witness to this fact when he quotes a verse from Ambrose’s hymn in the context of his own Christmas homily:

[Christ] came forth today like a bridegroom from his sacred chamber, and as the psalm continues, he exulted as a giant to run the course [Psalm 19:5]… Which course, if not the course of our mortality, which he was willing to share with us? … He came down, you see, and ran; he ascended, and took his seat. You know that, because you are in the habit of confessing it in the creed: “After he had risen, he ascended into heaven, he is seated at the right hand of the Father.” This course run by our giant was succinctly and beautifully turned into song by the blessed Ambrose, in the hymn you sang a few moments ago:

From the Father he came forth,

To the Father he returned;

His outward course to the realms of death,

His homeward course to the throne of God. (Sermon 372.2–3)As one might expect, Augustine’s preaching on this verse from Veni, redemptor gentium builds upon the biblical imagery in the verse immediately preceding it:

May he proceed from his chamber,

The royal hall of modesty,

The giant of twin substance

Keen to run the race.In this hymn verse, Ambrose efficiently interprets the mention of a “giant” in Psalm 19—a text evidently used in the Christmas liturgy of his (and Augustine’s) church—with reference to another pregnant passage pertaining to giants:

The Nephilim [“giants”] appeared on earth in those days, as well as later, after the sons of God had intercourse with the daughters of human beings, who bore them sons. They were the heroes of old, the men of renown. (Genesis 6:4)

Such a strange scriptural detail bespeaks, for Ambrose, the twofold nature—at once human and divine—of Christ, “the giant of twin substance” (or “our giant,” as Augustine endearingly calls him). It also calls to mind—in stark contrast to the circumstances of the Nephilim—the mystery of Christ’s virginal birth from Mary, “the royal hall of modesty.” Thus, with a single ingenious Christmas carol, Ambrose not only celebrates the mystery of Christ Incarnate, he also teaches his congregation how to interpret the Scriptures in Christ’s “new light” (cf. verse 8). It’s no wonder, then, that Saint Benedict wanted his monks to sing such a hymn—or that we sing it still today.

- [Hearken, you who rule Israel,

who sit above the Cherubim,

appear before Ephraim, rouse up

your power and come.] - Come, redeemer of the nations,

show the birth from the Virgin,

let every age marvel,

that such a birth was fitting for God. - Not from man’s seed,

but from a mystical breath,

the Word of God became flesh

and the fruit of the womb flourished. - The womb of the Virgin swelled,

while the seal of her modesty stayed,

the banner of virtues glittered,

and God dwells in his temple. - May he proceed from his chamber,

the royal hall of modesty,

the giant of twin substance

keen to run the race. - His procession from the Father,

his return to the Father;

his journey all the way to Hell,

his return to the seat of God. - O equal to the eternal Father,

robe yourself with the spoils of flesh,

strengthen the weakness of our body

with enduring virtue. - Now may your crib shine out

and night send forth new light

which no night may falsify

and will shine with lasting faith.

———–

Further reading/listening:

- Augustine of Hippo. Sermons 341–400 on Various Subjects. Translated by Edmund Hill. The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century. New City Press, 1992.

- Brian P. Dunkle. Enchantment and Creed in the Hymns of Ambrose of Milan. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Schola Cantorum Leipzig. “Veni, redemptor gentium.” (Traditional Latin hymn)

- Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles. “Come Thou Redeemer of the Earth.” (Modern English translation)

- Martin Luther, “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.” (16th century German translation)

- Johan Sebastian Bach. “Cantata Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland” (BWV 62). (Baroque chorale cantata)

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

- [Hearken, you who rule Israel,

-

Monastic Life: Tragedy or Comedy?

Monastic Life: Tragedy or Comedy?

In Timon of Athens, William Shakespeare tells the tragic tale of a man who discovers—only too late—that no good deed goes unpunished. As the play begins, the titular Timon is shown to be extravagantly wealthy and still more extravagantly generous. Assuming all men to be his friends, he hosts great banquets and bestows lavish gifts upon each guest. “Methinks I could deal kingdoms to my friends,” he declares, “and ne’er be weary” (2.221).

When his faithful steward informs him, however, that his treasury has run dry, Timon replies with boundless confidence in his former beneficiaries. “You mistake my fortunes,” he explains, “I am wealthy in my friends” (4.178–179). One by one, he appeals to them for financial assistance. Yet, one by one, each “friend” rebuffs him with a paper-thin excuse. In anger and despair, Timon then summons all his “mouth-friends” (11.88) to one final feast. Uncovering the dishes—which contain nothing but stones and steaming water—Timon utters an impassioned curse against all his guests: “Burn house! Sink Athens! Henceforth hated be / Of Timon man and all humanity!” (11.102–103)

He then flees the city, flings off his clothing, and makes for his new home in the wilderness—offering, on the way, a particularly unorthodox prayer:

Timon will to the woods, where he shall find

Th’unkindest beast more kinder than mankind.

The gods confound—hear me you good gods all—

Th’Athenians, both within and out that wall;

And grant, as Timon grows, his hate may grow

To the whole race of mankind, high and low.

Amen. (12.35–40)As far as externals go, Timon’s flight from the vanity of the world is strikingly similar to the experience of the early monks, also known as “the renunciants” (John Cassian, The Institutes, Book IV). He leaves the city and takes up residence within a cave; he strips off his clothing and walks about half-naked; he disdains rich food and instead digs for roots; he even takes a new name for himself: “I am Misanthropos,” he tells his first visitor, “and hate mankind” (14.49–53).

The early monks, however, differ from Timon in one all-important detail: their motivation. Each and every one spurned the world not out of hatred, but out of love.

In this respect, Saint Pachomius—the father of communal monasticism—provides a striking contrast to Timon of Athens. Before his conversion to Christianity, Pachomius—who had “hated evil” even from his youth (Life 3)—was forcibly conscripted by Roman troops and held captive in a military prison. Rather than growing resentful at this injustice, however, he focused instead on the beautiful witness of some Christians who came to minister to him in his distress. “Withdrawing alone in the prison,” he uttered a prayer that is the polar opposite of Timon’s:

O God, maker of heaven and earth, if you will look upon me in my lowliness, because I do not know you, the only true God, and if you will deliver me from this affliction, I will serve your will all the days of my life and, loving all men, I will be their servant according to your command. (5; emphasis added)

In time, he was freed from captivity, sought instruction in the Christian faith, and received baptism. “Then, moved by the love of God, he sought to become a monk” (6; emphasis added). Departing his city for the desert of Egypt, he apprenticed himself under an old ascetic named Palamon. For seven years he mortified his flesh—in much the same way as Timon of Athens—and stood “in the desert for prayer, asking God to deliver him and all men from the deceitfulness of the enemy” (11; emphasis added).

Coming one day to a deserted village, Pachomius “prayed to express his love of God” (12; emphasis added). In response, his vocation was vouchsafed to him by the Lord: “Stay here and build a monastery; for many will come to you to become monks” (12). By thus becoming a monk and founding a monastery—the seed for all future monastic communities—Pachomius fulfilled his earlier vow to the Lord: “loving all men, I will be their servant according to your command” (11).

If The Life of Timon of Athens is a tragedy—a portrait of one man’s plummet from prodigal generosity to hatred of the human race—then The Life of Saint Pachomius is its mirror image: a comedy (in the classical sense), concluding with one monk’s loving service to all men. Both men could be considered “monks” insofar as they were both “renunciants,” but only one fulfilled the greatest commandment of Christ: “love the Lord God with your whole heart, your whole soul and all your strength, and love your neighbor as yourself” (Luke 10:27; Rule of Benedict 4.1–2). And that has made all the difference.

———–

Further reading:

- William Shakespeare and Thomas Middleton. The Life of Timon of Athens. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- “The First Greek Life of Pachomius.” In Pachomian Koinonia: The Life of Saint Pachomius and His Disciples. Translated by Armand Veilleux. Cistercian Publications, 1980. Pages 297–423.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

Novels Are Not Just for Literature Professors... (Or: What Is Br. Ambrose Reading Now?)

Novels Are Not Just for Literature Professors… (Or: What Is Br. Ambrose Reading Now?)

Mount Angel Seminary began this, its 136th academic year, with a flourish. In a remarkable feat of literary dexterity, Dr. Katie Jo LaRiviere—associate dean and professor of literature—delivered an inaugural address that wove together sources as (seemingly) disparate as the poetry of Pope St. John Paul II, Pope Francis’ 2022 Apostolic Letter on liturgical formation, Desiderio Desideravi, and the 2014 science fiction film, Interstellar. The address reached its most moving moment, however, when Dr. LaRiviere described her own experience of reading a new novel: Chouette, by Claire Oshetsky. Acknowledging her initial lack of sympathy with the novel’s narrator, Dr. LaRiviere explained how she persevered on account of the author’s beautiful prose. Yet when she came to a scene in which the narrator relived a childhood trauma and sought solace through music, Dr. LaRiviere confessed to having “closed [her] eyes and wept”:

I wept for the character from whom I had felt so different, and even perhaps judgemental. I wept for her trauma, because I too, and each one of us, have faced traumatic moments. I wept because I too know how it feels to panic, to breathe my way out of it, to seek beauty as a remedy… I wept because together, though one of us is standing here in front of you in reality and the other is alive only in the pages of a novel, this character and I had joined in the communion that is possible in music, and in the healing that experiences of awe can provide.

Dr. LaRiviere went on to describe this experience both as an invitation and as a gift:

Through the novel’s invitation to go outside of myself, I ended up on the receiving end of a great gift: I was seen by the novel in a way I hadn’t been for many years, and in a way I needed to be seen to stave off the human anxiety of feeling truly alone in my experiences.

In this experience of deep reading, Dr. LaRiviere is certainly not alone. Pope Francis, too, described the phenomenon in a recently published letter “on the Role of Literature in Formation”: “In our reading,” the Pope explained, “we are enriched by what we receive from the author and this allows us in turn to grow inwardly, so that each new work we read will renew and expand our worldview” (3). He goes on to quote another celebrated appreciator (and creator) of literature, C.S. Lewis: “In reading great literature… I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do” (18).

This twofold dynamic of deep reading—invitation and gift, self-transcendence and self-discovery—was recently realized in my own engagement with a new novel (new to me, at any rate): In This House of Brede, by Rumer Godden. Set in the fictional English Abbey of “Brede,” the novel describes the day-to-day lives of Benedictine women as they deal with the petty jealousies, personality conflicts, and even public scandals that are part and parcel of all community life (yes, even religious life!). More meaningfully, though, the novel also depicts the mysterious and inexorable power of monastic life to cut through all our childish attempts at self-preservation and bring us to true conversion of life.

In one of the novel’s climactic scenes, the protagonist—Dame Philippa—had been avoiding (one might say religiously) a junior member of the community—Sister Polly (short for “Polycarp”)—on account of her tenuous relation to a traumatic event experienced many years prior. Unfortunately—or, rather, providentially—both sisters managed to catch chicken pox and were quarantined together. For nineteen days, Polly faithfully ministered to the much greater sufferings of Philippa, unknowingly heaping burning coals upon her head in the process (cf. Proverbs 25:21–22). Philippa, with a self-deprecating laugh at “my little puny self,” described her “virulent rash” as “the poison coming out,” and asked, half deliriously, “how many skins does one have to shed” (279–280)? At the end of her ordeal, though, she had been healed not only of her chickenpox, but also of her coldness and lack of charity toward Polly.

Just as Dr. LaRiviere was deeply moved by her reading of Chouette, so too was I moved by my reading of In This House of Brede. The precise details of Dame Philippa’s life were obviously quite different from mine—Philippa is a woman after all, and Brede is not Mount Angel—but the novel drew me out of myself to empathize with the struggles and secret grief of a character so believable as to make me wonder how many unperceived “Philippas” might exist in my own Abbey… At the same time, Philippa’s painful yet purifying experience of grace, mediated through Polly, was so akin to my own experience of life in community that I felt deeply seen and known by the novel’s author. I, too, am a “Philippa,” and I still have “many skins to shed” before I can truly “love from a pure heart” (1 Timothy 1:5).

Of course, Dame Philippa is not a real person—nor, for that matter, is the protagonist of Chouette, or any other character to be found in the pages of a novel. If, however, we make the effort to encounter them in an act of deep reading, “our hearts will swell with the unspeakable sweetness of love, enabling us to race along the way of God’s commandments” (Rule of Benedict, Prologue 49 [translated by Terrence Kardong]).

———–

Further reading:

- Katie Jo LaRiviere. “Reading Communion: Finding Home in Liturgy and Literature.” Mount Angel Seminary Inaugural Address. August 26, 2024.

- Pope Francis. “Letter of His Holiness Pope Francis on the Role of Literature in Formation.” July 17, 2024.

- Rumer Godden. In This House of Brede. Viking Press, 1969.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

Lovers of the Place

Lovers of the Place

Saint Benedict wrote his monastic rule for “cenobites, that is to say, those who belong to a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot” (RB 1.2). Because these qualities differentiate Benedictine monks from other kinds of consecrated Christians, Benedict prescribed three unique vows for his spiritual sons and daughters: “stability, fidelity to monastic life, and obedience” (RB 58.17). These vows, though, are novel not for what they omit—the “evangelical counsels” of poverty and chastity are presumed within the vow of “fidelity to monastic life”—but for the unusual element they require: stability.

The Benedictine vow of stability does not mean that modern monks are barred from association with the doctor, the dentist, or the DMV (if only life were that simple!). It does mean, however, that a monk will never be “moved” or “transferred to a new assignment” (barring very extraordinary circumstances). His home, for the rest of his life, will be the monastery.

Since the monk’s stability is freely chosen, it tends to foster a particular fondness for the place in which he is planted—regardless of that place’s natural attractiveness. When Antony of the Desert, for instance, retreated to his “inner mountain,” deep in the deserts of Egypt, he “fell in love with the place… Looking on it as his own home, from that point forward he stayed in that place” (Athanasius, Life of Antony 50). A similar story was told about Saint Benedict’s early days as a hermit. After a group of monks—in name only—attempted to poison “the man of God,” Benedict got up and “went back to the wilderness he loved, to live alone with himself in the presence of his heavenly father” (Gregory the Great, Dialogues 2.3). For both Antony and Benedict, the practice of monastic stability made even the wilderness loveable.

This same spirit of stability was exemplified five centuries later by the saintly founders of the Cistercian Order (i.e., the first Benedictine reformers): Robert, Alberic, and Stephen. Departing from the lax monastic practices of their first monastery for the forested wilderness of France, they discovered a place that, “because of the thickness of grove and thornbush,” was “inhabited only by wild beasts” (Stephen Harding, “Exordium Parvum,” Chapter 3). They realized, however, that “the more despicable and unapproachable the place was to seculars, the more suited it was for the monastic observance they had already conceived in mind.” So they set to work, “cutting down and removing the dense grove and thornbushes,” and “began to construct a monastery there.” This monastery became Cîteaux Abbey, and its third abbot, Stephen Harding, is famously remembered as “a lover of the Rule and of the place” (Chapter 17). His account of Cîteaux’s founding was written for subsequent generations of monks in order that “they may the more tenaciously love both the place and the observance of the Holy Rule there” (Prologue).

In many ways, the monks of Mount Angel differ quite a bit from the founding fathers of Cîteaux (not to mention Antony and Benedict). We’re not Cistercians, for starters. And our “place”—with its majestic view of the Cascade Mountains and the Willamette Valley—could never be described as “despicable and unapproachable.” But we identify with the first Cistercians in at least one sense: we, too, are “lovers of the Rule and of the place.” In fact, we are lovers of the place principally because we were first lovers of the Rule. None of us vowed stability on this hill in rural Oregon simply because of its natural beauty; rather, we discovered here a place where we could authentically seek and find God, serving together “under a rule and an abbot.”

Only after putting down roots in the rich soil of monastic stability is our love of this place elevated to the supernatural plane. On a natural level, everyone marvels at the majestic view from our “holy mountain.” On a supernatural level, however, only the monks of Mount Angel (and, perhaps, our oblates and employees) recognize that this mountain is the very one of which the psalmist speaks: “O Lord, who can be a guest in your tent? Who can dwell on your holy mountain?” (Psalm 15:1; cf. RB Prologue 23) Similarly, all our guests can attest that our sunrises are spectacular. Yet, when the sun rises right behind Mount Hood on August 6, the Feast of the Transfiguration, only the monks of Mount Angel feel cosmically convinced that we are the disciples whom Jesus has led “up a high mountain,” “gazing,” in all our daily prayer and work, “with unveiled face on the glory of the Lord” (Matthew 17:1; 2 Corinthians 3:18). Even during the wet, gray days of winter and the summers of 115-degrees-and-no-air-conditioning, we resolutely repeat the words of holy Jacob: “How awesome this place is! This is nothing else but the house of God, the gateway to heaven!” (Genesis 28:17)

Photo courtesy of Br. Lorenzo Conocido, OSB.

———–Further reading:

- Stephen Harding, et al. “Exordium Parvum.” Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance. https://ocso.org/resources/foundational-text/exordium-parvum/.

- Athanasius of Alexandria. Athanasius: The Life of Antony and the Letter to Marcellinus. Translated by Robert C. Gregg. The Classics of Western Spirituality. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1980.

- Jason M. Brown. Dwelling in the Wilderness: Modern Monks in the American West. San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press, 2024.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

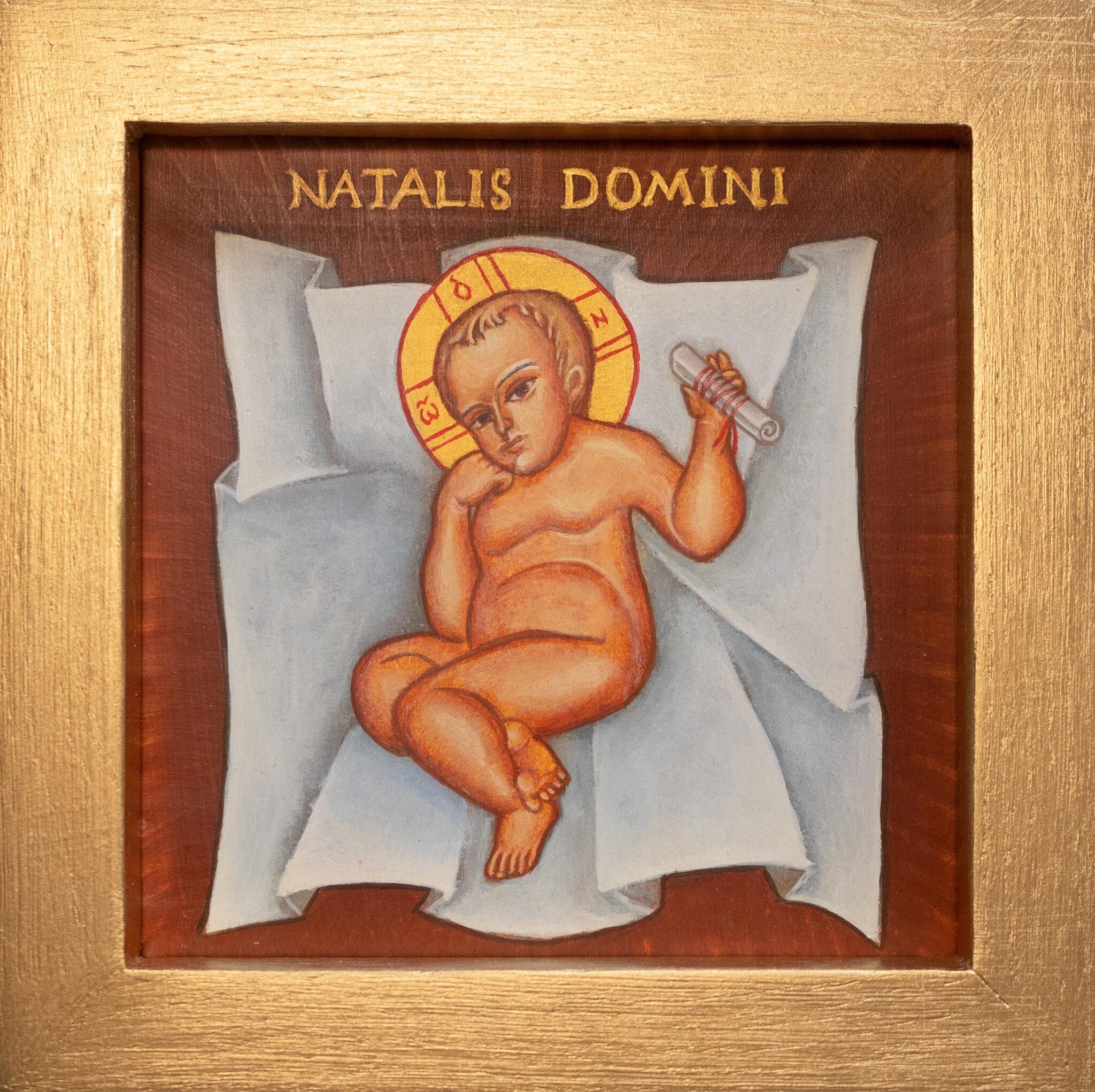

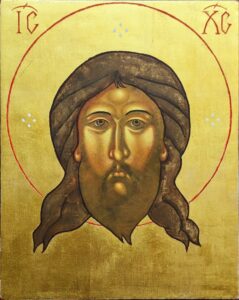

Icons of Humility

Icons of Humility

What do Jesus, Mary, and Saint Benedict have in common? Quite a lot, actually. But if their spiritual similarities had to be summed up in a single word, recent events at Mount Angel would make the choice clear: humility.

This particular combination of spiritual exemplars was suggested by the second-annual Summer Iconography Retreat which took place at the Abbey from July 7–12. Beginning students were assigned to paint the face of Christ (“the holy Mandylion”), Intermediate students painted the Blessed Virgin Mary (The “Hagiosoritissa,” or “intercessor”), and Advanced students painted Saint Benedict. This year, I found myself—along with Brothers Alfredo, Isaiah, and Sherif—in the intermediate class, so I spent the week painting Mary’s image. In my experience, however, “painting” wasn’t quite the right word to describe the process… Nor, for that matter, was “writing” (the word iconographers usually use to describe their creation of an icon). It felt more like I was receiving the image. God was the real artist; I was just his brush.

This feeling was produced, in large part, by the process employed in the icon’s creation. For the foundational painting of Mary’s skin and garment, I was instructed to use a “lake” technique. Rather than adding pigment in fine, controlled brush strokes, I

flooded large areas with “lakes” of translucent egg tempera. As the water evaporated and the pigment settled onto the board beneath, it produced a dynamic effect that was utterly unique and unrepeatable. I thus had no control over the underlying tone of Mary’s skin or the subtle pattern in her garment. Later on, when the time came for me to paint fine details and I inevitably made mistakes, my own anxious efforts to quickly correct them seemed only to make matters worse. I had no choice but to acknowledge the wisdom in Saint Benedict’s dictum (given in a different context, but just as fitting here): “If you notice something good in yourself, give credit to God, not to yourself, but be certain that the evil you commit is always your own and yours to acknowledge” (RB 4.42–43). In the end, my contribution to the icon of Mary was no different than Mary’s contribution to the Incarnation of Christ: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38).

flooded large areas with “lakes” of translucent egg tempera. As the water evaporated and the pigment settled onto the board beneath, it produced a dynamic effect that was utterly unique and unrepeatable. I thus had no control over the underlying tone of Mary’s skin or the subtle pattern in her garment. Later on, when the time came for me to paint fine details and I inevitably made mistakes, my own anxious efforts to quickly correct them seemed only to make matters worse. I had no choice but to acknowledge the wisdom in Saint Benedict’s dictum (given in a different context, but just as fitting here): “If you notice something good in yourself, give credit to God, not to yourself, but be certain that the evil you commit is always your own and yours to acknowledge” (RB 4.42–43). In the end, my contribution to the icon of Mary was no different than Mary’s contribution to the Incarnation of Christ: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord. May it be done to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38).Providentially, this very theme was highlighted on July 11—the penultimate day of our retreat—in Abbot Jeremy’s homily for the Solemnity of Saint Benedict. He noted that Benedict himself was remembered as “a gentle and humble man”; that the longest chapter of his Holy Rule (chapter 7) “is a program for teaching us how to imitate Christ, who is humility itself”; and that “the whole of the monastic life centers around the question of the monk’s growth in humility.” I, myself, wasn’t working on icons of Christ or Saint Benedict that week, but my work on Mary (or, more accurately, her work on me) had eloquently exemplified their teaching and inscribed a glimmer of their humility upon my heart.

———–

Further reading / viewing:

- Natalie Wood. “Discovering Serenity in Beauty: Finding What You Seek at the 2024 Iconography Retreat at Mount Angel Abbey.” Classical Iconography Institute.

-

Abbot Jeremy Driscoll, O.S.B., “Homily on the Solemnity of St. Benedict”.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

What’s in a Name? (Or: What’s in a Monastic Community Retreat?)

What’s in a Name?

(Or: What’s in a Monastic Community Retreat?)Us monks were rather taken aback by the topic of our recent community retreat (May 20–24). Its director, Fr. Kevin Grove, CSC, had previously delivered a series of lectures for the Mount Angel Institute in which he elucidated Augustine’s Expositions on the Psalms—evidently one of his specialties. We thus expected something similar for our monastic retreat. What we got, however, was just as delightful as it was shocking: eight spiritual conferences on four short stories by the famous Southern novelist, Flannery O’Connor.

The four stories upon which we focused were some of Flannery’s most famous compositions: “Revelation,” “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “Parker’s Back,” and “A Temple of the Holy Ghost.” Of these, however, “Parker’s Back” seemed to resonate most with the monastic community. This was, I suspect, because the story touches on a deeply monastic theme, namely, the acceptance of one’s name. (I won’t spoil some of the story’s more central elements in the hope that you might read it for yourself.)

When a man takes monastic vows, he also takes (or, more accurately, is given) a new name—a Christian name, one that expresses his truer and deeper identity in relationship to God. The reception of a monastic name mirrors God’s renaming of the patriarchs—e.g., Abram became Abraham (Genesis 17:5) and Jacob became Israel (Genesis 32:29)—and claims what Christ promised to each believer in the book of Revelation: “To the victor I shall give… a white amulet upon which is inscribed a new name, which no one knows except the one who receives it” (2:17).

In “Parker’s Back,” however, the eponymous protagonist spends most of the story rejecting his given name. “Parker,” as it turns out, is only a surname. The name he received at his baptism was Obadiah Elihue. This name, which means “servant of God,” “stank in Parker’s estimation” because, as he explained to a tattoo artist, “I ain’t got no use for [religion].” As a result, “he had never revealed the name to any man or woman”… until, that is, he met his future wife.

At his second encounter with Sarah Ruth, Parker introduced himself as “O. E.,” but he stubbornly refused to divulge his full name. Sarah, however, persisted, asking three times, “What does the O. E. stand for?” Only after Sarah had sworn “on God’s holy word” never to “tell nobody” did Parker finally relent. “He reached for the girl’s neck, drew her ear close to his mouth and revealed the name in a low voice.” “Obadiah,” Sarah whispered, and “her face slowly brightened as if the name came as a sign to her.”

Sarah’s threefold questioning regarding Parker’s true name is significantly echoed in the climax of the story. When Parker came home late one night (you’ll have to read the story to find out why…), he discovered the door to his house barred. “Who’s there?” asked Sarah from the other side. “Me,” Parker said, “O.E.” “I don’t know no O.E.,” she replied. Parker protested, banging on the door and exclaiming, “O.E. Parker. You know me.” Still waiting for the magic words, Sarah repeated her question a second and then a third time: “Who’s there?” Finally, Parker bent down and whispered into the keyhole: “Obadiah… Obadiah Elihue!” In this final acceptance of his true name, Parker “felt the light pouring through him, turning his spider web soul into a perfect arabesque of colors, a garden of trees and birds and beasts.”

Both scenes of threefold questioning result in Parker’s acceptance of his true name—and also the grace that comes along with it. In this way, they mirror the moving exchange between Peter and the risen Christ at the conclusion of Saint John’s Gospel. Echoing Peter’s previous three denials of him (cf. John 18:15–27), Jesus questions him three times:

Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Feed my lambs.” He then said to him a second time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord, you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Tend my sheep.” He said to him the third time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” Peter was distressed that he had said to him a third time, “Do you love me?” and he said to him, “Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.” [Jesus] said to him, “Feed my sheep.” (John 21:15–17)

In addressing Peter as “Simon, son of John,” Jesus subtly implied that Peter had renounced not only Jesus himself, but also the name that Jesus had given to him (cf. Matthew 16:18). Yet by eliciting Peter’s threefold confession of love and commissioning him to care for his sheep, Jesus was, in a way, helping “Simon, son of John” rediscover his identity as “Peter,” the “rock” upon whom Jesus would build his church.

Like Obadiah Elihue Parker and Simon Peter, monks experience the day-to-day struggle between the “old man”—who is cowardly and prone to sin—and the “new man, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness” (Ephesians 4:23–24). In the midst of this daily identity crisis, our religious names stand as silent sources of grace, drawing us inexorably back to the knowledge of who—or, better yet, whose—we really are.

———–

Further reading:

- Flannery O’Connor. The Complete Stories. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971. [“Parker’s Back” can be accessed electronically at tinyurl.com/parkers-back]

- Flannery O’Connor. The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988.

- Flannery O’Connor. Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1970.

- Flannery O’Connor. A Prayer Journal. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

- Ethan Hawke (director). Wildcat. 2023.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

"If It’s a Symbol, To Hell With It!"

“If it’s a symbol, to hell with it!”

– Flannery O’ConnorIn a significant scene from the new film about Flannery O’Connor (“Wildcat”), the young Southern writer finds herself at the head of a table—reminiscent of Christ at the Last Supper—surrounded by a group of literary elites. Aware that Flannery is a devout Catholic, their conversation quickly turned toward the Blessed Sacrament. “Do Catholics really believe,” one of them asked, “that they’re eating the body of Christ—like cannibals?” The woman sitting beside Flannery, attempting to be diplomatic, described how she understood the Eucharist to be “a lovely, expressive symbol.” Flannery, never one to sugarcoat the truth, interjected with what has come to be her most-quoted line: “If it’s a symbol, to hell with it!”

Flannery elaborated on her abrupt defense of the Blessed Sacrament in one of her published letters: “That was all the defense I was capable of but I realize now that this is all I will ever be able to say about it, outside of a story, except that it is the center of existence for me; all the rest of life is expendable” (Habit of Being, 125). For Flannery, the Eucharist was not a symbol of something else; instead, “all the rest of life” was a symbol of the Eucharist.

This vision of reality was articulated more fully in one of Flannery’s most famous stories, “A Temple of the Holy Ghost” (providentially one of the four stories we studied during our recent community retreat). In the story’s final scene, its young protagonist (a delightfully sassy little girl) is dragged into Eucharistic Benediction by a “big moon-faced nun” from the fictional convent of “Mount St. Scholastica.” During the chanting of the Tantum Ergo, the child began her mechanical litany of prayers: “Hep me not to be so mean… Hep me not to give her so much sass. Hep me not to talk like I do.” But at the moment the priest elevated the monstrance, the child’s mind unexpectedly wandered to the “freak” she had heard about from the local fair—in this case, a person who happened to be “a man and woman both.”

Earlier in the story, the child had dreamt of this “freak” as the presider at a Eucharistic liturgy. His/her lines from the circus performance—“God made me thisaway and I don’t dispute hit”—bled seamlessly into his/her Christian exhortation: “Raise yourself up. A temple of the Holy Ghost. You! You are God’s temple, don’t you know? Don’t you know? God’s Spirit has a dwelling in you, don’t you know?”

This vision draws together shocking contraries: circus and church, male and female, bread and body, sin and grace. But all of these paradoxes point ultimately to Jesus Christ, the God-man, who alone holds them together in himself. As St. Paul once said: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28). And again: “he is our peace, he who made both one and broke down the dividing wall of enmity, through his flesh” (Eph 2:14).

As the child was being driven home from the convent that evening, she looked out the window and saw the sun. The “huge red ball” appeared to her “like an elevated Host drenched in blood.” As it sank, “it left a line in the sky like a red clay road hanging over the trees.” Her experience at Mount St. Scholastica had opened her eyes to see the whole created order, in all its majesty and mystery, as a road leading straight to the source of all grace: the most precious body and blood of Christ.

———–

Further reading:

- Flannery O’Connor. The Complete Stories. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971. [“A Temple of the Holy Ghost” can be accessed electronically at tinyurl.com/a-temple-of-the-holy-ghost]

- Flannery O’Connor. Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1970.

- Flannery O’Connor. The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988.

- Flannery O’Connor. A Prayer Journal. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

- Ethan Hawke (director). Wildcat. 2023.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

“One Body, One Spirit in Christ” (Or: Did You Know You’re Speaking in Tongues?)

“One Body, One Spirit in Christ” (Or: Did You Know You’re Speaking in Tongues?)

“The Spirit blows where he wills” (Jn 3:8). That is to say: it is notoriously difficult to identify the Spirit’s nature and activities. Just take, for instance, the famous account from the Acts of the Apostles in which the Spirit first descended, in dramatic fashion, upon Christ’s disciples:

They were all in one place together. And suddenly there came from the sky a noise like a strong driving wind, and it filled the entire house in which they were. Then there appeared to them tongues as of fire, which parted and came to rest on each one of them. And they were all filled with the holy Spirit and began to speak in different tongues, as the Spirit enabled them to proclaim. (Acts 2:1–4)

Such dramatic depictions of the Spirit usually leave us, like the original onlookers, “astounded and bewildered” (Acts 2:12). Although most of us believe that we received the Holy Spirit at our Baptism and Confirmation, very few of us have experienced such supernatural manifestations of the Spirit’s presence as “a strong driving wind,” “tongues as of fire,” or the ability to “speak in different tongues.” “Why,” one might reasonably ask, “aren’t I speaking with the tongues of all nations?” (Augustine, Sermon 267.4)

As the citation for the preceding question suggests, Saint Augustine had long ago wondered the same thing. If the Holy Spirit had manifested himself so dramatically to Christ’s first-century disciples—and with such impressive results (cf. Acts 2:41)—then why did he cease to do so by the time of Augustine’s fourth-century Church (let alone our twenty-first century Church)? In the course of his preaching on the feast of Pentecost, Augustine offered an answer for his assembly:

Among you, after all, is being fulfilled what was being prefigured in those days, when the Holy Spirit came. Because just as then, whoever received the Holy Spirit, even as one person, started speaking all languages; so too now the unity itself is speaking all languages throughout all nations; and it is by being established in this unity that you have the Holy Spirit; you that do not break away in any schism from the Church of Christ which speaks all languages. (Sermon 271)

Augustine’s explanation represents an imaginative re-reading of the Pentecost account in Acts 2. As he interpreted the scene, it was not a multitude of diverse individuals who spoke in different tongues on that day, but “one person was speaking in the tongues of all nations,” namely, “the unity of the Church” (Sermon 268.1). A single corporate entity, composed of individuals “from every nation, race, people, and tongue” (Rev 7:9), is miraculously constituted and sustained in unity by the power of the Holy Spirit. And every believer who is now in communion with this mystical body, the Church of Christ, is continually being filled with the same Holy Spirit.

Such an interpretation of Acts owes just as much to Augustine’s personal lectio divina on the biblical text as it does to the liturgical context of its proclamation. Because his sermon was being preached in the midst of a Eucharistic celebration—as his North-African congregation celebrated the Solemnity of Pentecost—Augustine could not have failed to connect the action of the Holy Spirit in Acts with the action of the Holy Spirit in the course of the Eucharistic Prayer.

Although the words of Augustine’s Eucharistic Prayer likely differed a bit from the Eucharistic Prayers we use today, they certainly contained one very important element: the epiclesis. This Greek term—translated literally as “calling down upon”—refers to the point in the prayer when the priest petitions the Father to send the Spirit upon the gifts which have been presented, thus transforming them into the Body and Blood of his Son.

This moment is most explicit in the Roman Missal’s “Eucharistic Prayer III” (but it is nonetheless present in all of them). Shortly after the Sanctus (“Holy, Holy, Holy”), the priest “joins his hands and, holding them extended over the offerings” prays the following words:

Therefore, O Lord, we humbly implore you: / by the same Spirit graciously make holy / these gifts we have brought to you for consecration, / that they may become the Body and Blood / of your Son our Lord Jesus Christ, / at whose command we celebrate these mysteries.

This, however, is not the only epiclesis in the Eucharistic Prayer. A little later on, following the Memorial Acclamation (“the mystery of faith”), the priest continues: “grant that we, who are nourished / by the Body and Blood of your Son / and filled with his Holy Spirit, / may become one body, one spirit in Christ.”

Thus, in the course of the Eucharistic Prayer, the Spirit is twice invoked to work two related wonders: the transformation of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ, and the transformation of the gathered assembly into that very same Body. Every Mass, then, is like a new Pentecost—a miracle of unity wrought by the Spirit. Whether or not we experience other miraculous manifestations of the Spirit’s presence, we can be confident that He is the means by which we are “all in one place together” (Acts 2:1).

———–

Further reading:

- Augustine. Sermons (230–272B) on Liturgical Seasons. Translated by Edmund Hill, O.P. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 1993.

- Jeremy Driscoll. What Happens at Mass. Revised Edition. Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2011.

– Br. Ambrose Stewart, OSB

-

"The King Has Brought Me Into His Bedchamber"

“The King Has Brought Me Into His Bedchamber”

The climax of the Lenten season—indeed, of the entire liturgical year—is the Sacred Paschal Triduum. This single liturgical event “solemnly celebrates the greatest mysteries of our redemption” through the consecutive commemoration of “three days” (triduum, in Latin): Thursday of the Lord’s Supper, Friday of the Passion of the Lord, and Holy Saturday, which culminates with the Easter Vigil in the Holy Night (Roman Missal, “The Sacred Paschal Triduum,” 1). In the heart of this most holy of liturgies, the Church fittingly celebrates the sacraments of Christian Initiation, administering Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist to the newest members of Christ’s mystical body.

During the first centuries of the Church, the celebration of these sacraments—and the liturgy in which they were administered—was often shrouded in secrecy. Those who underwent the sacred rites of initiation were meant to experience them first—in all their vivid and very memorable details—and only later come to understand the significance of what they had experienced. This generally happened by means of mystagogical catechesis (words of Greek origin meaning “leading into a mystery” and “oral instruction”). This was a form of liturgical preaching in which the priest who had initiated new Christians would explain to them, in the days following the Easter Vigil, the meaning of each ritual element that they had experienced during that holy night.

While many mystagogical preachers (or “mystagogues”) preferred to nourish their “newborn infants” with “pure spiritual milk” (1 Pt 2:2)—that is to say, with “the basic elements of the utterances of God” (Heb 5:12)—Ambrose of Milan was different. In his two surviving sets of mystagogical catecheses, On the Mysteries and On the Sacraments, Ambrose explained the meaning of the Church’s sacred rites of initiation with reference not only to the simplest or most straightforward Scripture passages; he also fed his spiritual infants with the “solid food” (Heb 5:14) of the Song of Songs—arguably the most “mature” book in the biblical canon on account of its overtly erotic imagery.

As shocking as this may sound, however, there was a method to Ambrose’s madness. Beneath the Song’s “R-rated” veneer, the Christian mystical tradition had long discerned a deeper significance in this inspired text. Origen of Alexandria expressed it best in his third-century commentary on the Song:

It seems to me that this little book is an epithalamium, that is to say, a marriage-song, which Solomon wrote in the form of a drama and sang under the figure of the Bride, about to wed and burning with heavenly love towards her Bridegroom, who is the Word of God… But this same Scripture also teaches us what words this august and perfect Bridegroom used in speaking to the soul, or to the Church, who has been joined to Him. (Prologue, 1; emphasis added)

When thus read in a Christian key, the Song’s fleshly eroticism is transposed from a near occasion of sin to a clear communication of the Church’s sublime vocation, namely, spousal union with Christ.

This spousal union—as Ambrose’s mystagogical preaching emphasizes—is not just “for the mature” (Heb 5:14), but for every Christian, and it begins with the sacrament of baptism. When each new believer comes up from the water, Ambrose assigns to him or her the words of Solomon’s swarthy Bride from the Song of Songs: “I am black but beautiful, O ye daughters of Jerusalem”—which means, according to Ambrose, “black through the frailty of human condition, beautiful through grace” (The Mysteries, 7.35; quoting Sg 1:14). Suddenly Christ enters the dialogue, speaking as the Bridegroom of the baptized soul: “Behold, thou art fair, my love, behold thou art fair, thy eyes are as a dove’s”—and the dove, Ambrose reminds us, is a symbol of the Holy Spirit (7.37; quoting Sg 4:1). Christ then invites his Bride to receive the sacrament of Confirmation: “‘Place me as a seal upon thy heart,’ that thy faith may shine with the fulness of the sacrament” (7.41; quoting Sg 8:6). Finally, the Bride consummates her union with Christ through her reception of the Eucharist:

Your soul sees that it is cleansed of all sins, that it is worthy so as to be able to approach the altar of Christ—for what is the altar of Christ but a form of the body of Christ—it sees the marvelous sacraments and says: ‘Let him kiss me with the kiss of His mouth’… ‘The king has brought me into his bedchamber’… (On the Sacraments 5.2.5–11; quoting Sg 1:2–4)

Whether or not a newly-initiated Christian can fully grasp the grandeur of Ambrose’s mystagogical catecheses—or the intimate imagery of the Song of Songs—those of us who have long been baptized can certainly benefit from the deepening reflection they invite on the meaning of our own sacramental initiation. As we witness (or at least pray for) others undergoing these rites during the Sacred Paschal Triduum, may we too be drawn more deeply into the mystery of Christ’s passionate love for his Bride, the Church (cf. Eph 5:22–33).

———–

Further reading:

- Ambrose of Milan. “The Mysteries” and “The Sacraments.” In Theological and Dogmatic Works. Translated by Roy J. Deferrari. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1963.

- Jeremy Driscoll. Awesome Glory: Resurrection in Scripture, Liturgy, and Theology. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2019.

- Origen of Alexandria. The Song of Songs, Commentary and Homilies. Translated by R.P. Lawson. Mahwah, NJ: The Newman Press, 1957.